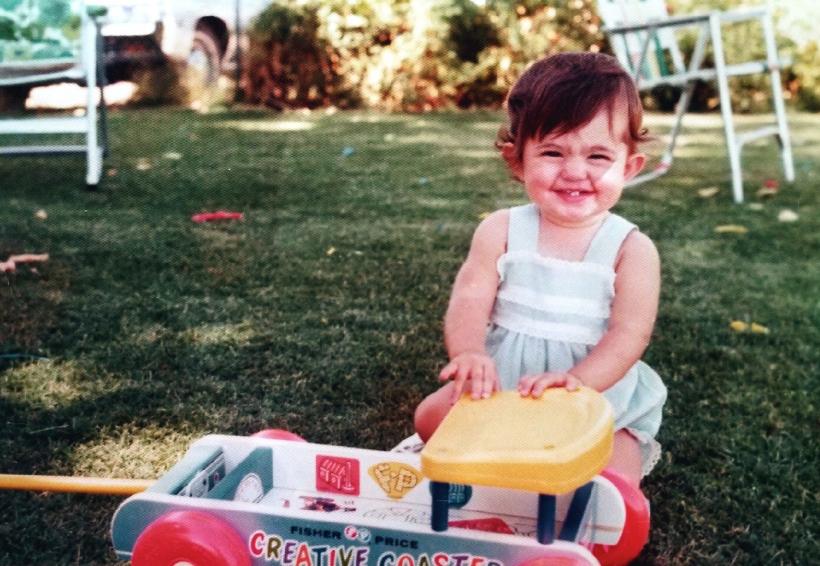

We never learned what was normal because we never saw normal

When I was little, I thought Pepto Bismol was magic medicine; a chalky miracle elixir, it could fix anything. Nausea, heartburn, indigestion, upset stomach, diarrhea, hangover, drunk but not yet hung over — it was the snake oil of a hundred uses. I grew up with a eight ounce bottle of pink Pepto in my fridge, situated between the Thousand Island dressing and ketchup — as if it wasn’t at all weird to have a bottle of pink Pepto in your fridge like a condiment for stomach upset.

The recommended dose of Pepto Bismol is 30 ml, but you can drink it from a bendy straw, sticky with the lip marks of last night's Covergirl No. 372 Divine Wine, until you either vomit or pass out — or vomit then pass out. You can call out to your eight-year-old only daughter, rousing her from her bed, which should feel safe but doesn’t. You ask her for your Pepto with a straw and a hot washcloth to wipe away whatever mascara the tears didn’t take when you were in your third stage of drunkenness the night before — the one your eight-year-old daughter will grow up and call “hysterical weeping for no apparent reason.”

When I was little, I thought it was normal for moms to drink and drink tequila like it was meant to quench thirst, until they cried off 90% of their mascara, and drank Pepto with a straw and then vomited and passed out. I thought it was normal for eight-year-olds to bring their moms hot washcloths and pink Pepto with straws and small bathroom trash cans to catch their vomit.

When I was little, I thought it was normal for little girls to be mothers to their mothers.

I didn’t see it as mothering then. The Pepto and washcloths and trash cans were just part of my youth like Barbies and dress-up and board games were part of the youth of the kids I wanted to play with but never did because I was too busy being a mom to my mom to be a kid with other kids. Other kids played mommy with their dolls. I played mommy with my mommy — bringing her food in bed, answering the phone and lying about what she was doing, patting her forehead with a damp cloth while she wretched the remnants of a night of margaritas, down to the bile in the bottom of her stomach, down to the emptiness that wouldn’t be filled.

You Might Also Like: 10 Things The Adult Child Of An Addict Wants You To Know

I mothered my mother until I didn’t have it in me to do it any longer. By the time I stopped mothering my mother, I was a mother to five kids of my own. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to mother her any longer, it was that I couldn’t mother her any longer. I couldn’t scoop her up and take her to the ER. I couldn’t give her money or pay her bills or move her into my garage or worry about whether or not she was dead in her apartment and not just ignoring my phone calls like people sometimes do when they are either too drunk to talk or too sober to listen.

One day she called me for help, crying and slurring and saying her husband had beaten her. I went to her house and found her passed out on the sofa in her hurricane of an apartment, an empty handle of vodka in her filthy kitchen sink, a stainless steel bowl, full of the vodka her body had rejected in a physiological act of saving her life, on the floor next to the sofa she was passed out on. I threw the empty bottle of off-brand vodka at her, shocking her into a screech or disbelief. I threw a pillow and a blanket and whatever else I could get my hands on to throw in her direction, not because I wanted to hurt her because I wanted her to stop hurting me. Words came out of me like vomit, the incoherent screams of the child inside me looking at the child sitting sullen in front of her.

That day was the day I stopped being her mother.

While I was mothering my mother — burying cigarettes in the front yard, diluting tequila with water — I was also mothering myself. I walked to the grocery store to buy candy bars and paperback romance and horror novels off the carousel rack by the register. I hid in my room and read Stephen King and drank Coca-Cola from tall glass bottles. I dug through my mother's nightstand, rading wrinkled copies of Playboy and Penthouse until the things I saw that I shouldn't have seen were burned into my seven-year-old brain. I ate Chef Boyardee ravioli. I tried to teach myself to make scrambled eggs. I burnt scrambled eggs. I burnt my hand. I almost burnt down the kitchen.

I wasn't a very good mother to myself, but I was a better mother than she was.

I didn't know I was mothering myself any more than I knew I was mothering her; I wouldn't learn that until much later. When I finally did learn it, I still wouldn't admit it. When I admitted it, I still wouldn't give myself any grace for it. That’s what the children of addicts do. We don’t give ourselves any grace because we didn’t do a very good job raising our parents as our children. Our kids didn’t grow up and move out and become productive, responsible members of society. They just lived with us until we moved away from them or they moved away from us, or they literally killed themselves by ruining their livers or we metaphorically killed ourselves with the crushing weight of unmet expectations.

We never learned what was normal, because we never saw normal, so normal was a thing we defined for ourselves and consequently also a thing we were usually wrong about.

We seek perfection because we have a misguided, yet deeply held belief that if we are perfect we will be lovable and if we are lovable we will be worthy of our parent’s sobriety.

We are controlling because exerting control over our surroundings is the only way we can feel safe and we have never felt safe.

We never felt safe because a small child can’t feel safe when their protector is embodying the role of their child.

We feel guilty about caring for ourselves because our parents taught us through their inaction that we were born to be caregivers to them.

We are constantly seeking approval from the people around us because no one ever told us we were doing a good job.

We want so desperately to be doing a good job.

We did a great job being our own mothers, but no one ever told us because they either didn’t see it, or didn’t want to admit it, because if they saw it or admitted it they would also have to admit that they didn’t do anything about it which would make them both complacent and complicit.

And now we are grown. Some of us are mothers to our own children. Some of us know we were our own mothers and our mother's mothers and our siblings' mothers. Some of us don't know or don't want to know because knowing that we didn't have a mother will only drive the knife deeper into the child inside us that never was allowed to be a child in the first place.

We thought it was normal to mother our mothers.